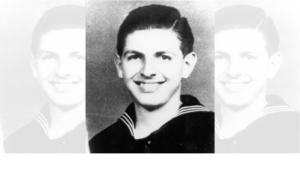

When automobiles first started tearing through American streets a century ago, they weren’t exactly welcome. One of the main problems was that they were killing children: in 1921 alone, 286 children in Pittsburgh, 130 in Baltimore, and 97 in Washington, D.C. Cities memorialized the dead with monuments and solemn marches. A safety council in Detroit commemorated traffic deaths by ringing bells at city hall and churches; another in Brooklyn put up a “Death-O-Meter” near a major traffic circle that kept a running tally of those injured or killed.

It wasn’t just in cities. At the beginning of the 20th century, rural residents revolted as drivers of “horseless carriages” rammed into their livestock and their neighbors. Across the country, they threw stones and dung at cars, shot at them, and trapped them in ditches dug across roads, or with ropes and wires strung between trees.

The arrival of automobiles was at first greeted with skepticism that they could ever replace horses, and then shock at the dangers they posed. Newspapers in the early 20th century called drivers “killers” and “remorseless murderers.” Cars weren’t seen as necessities, but rather the dangerous playthings of those wealthy enough to afford them. Today, media coverage defaults to the passive voice and calling crashes “accidents,” even as they continue taking lives — more than 39,000 people just last year in the United States.

This history of hostility to cars has been largely forgotten. “There’s the myth that the Model T rolled off the assembly line, and it was love at first sight,” said Doug Gordon, co-author of the new book Life After Cars: Freeing Ourselves from the Tyranny of the Automobile. Gordon wrote the book, an accessible account of the collective damage the automobile has brought to the world, with his fellow hosts of “The War on Cars” podcast, Sarah Goodyear and Aaron Naparstek.

It’s part of a growing opposition to car culture in the literary world — a trend that suggests more people are willing to entertain these criticisms than in previous years, at least by publishers’ estimations. September brought the release of Roadkill: Unveiling the True Cost of Our Toxic Relationship with Cars, a philosophical book arguing that cars don’t represent freedom, as we’ve been told, but constraint. Depending on cars drains our bank accounts, limits our transportation options, and locks in damage to our health and the environment. Roadkill was published the same day as Saving Ourselves from Big Car, a condemning investigation of the way automakers, oil companies, and related industries gained control of the road to rake in profits, no matter the consequences.

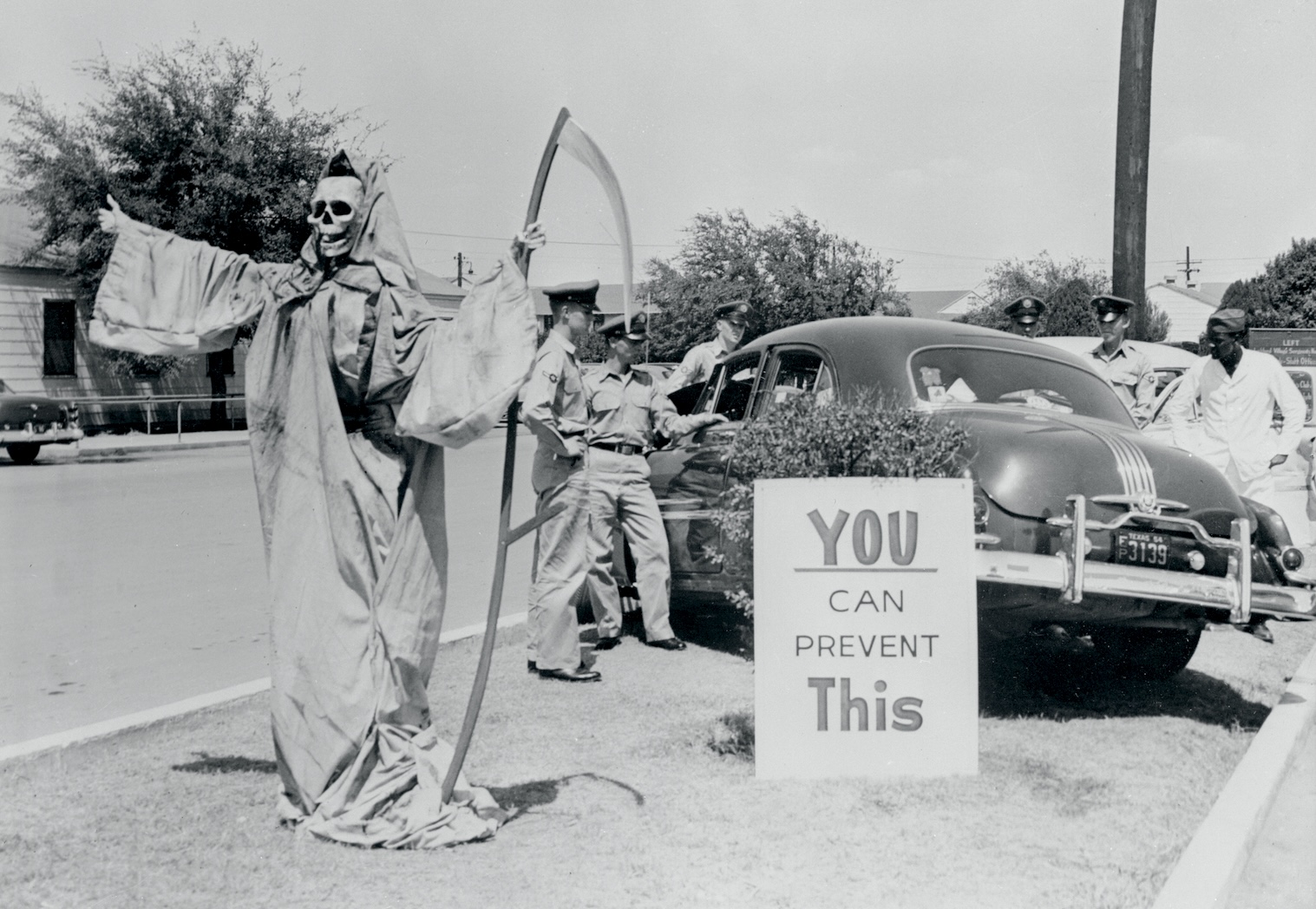

The facts about cars are alarming: Far more Americans have died from car crashes than from all the wars the United States has fought. The average driver in the U.S. spends more than three-quarters of a million dollars on cars in their lifetime. If the fleet of SUVs around the globe were a country, they would be the world’s fifth-largest emitter of carbon dioxide, behind Russia and ahead of Japan.

None of these problems are new — in fact, people have been warning us about many of them for decades. So why is it so easy to ignore these glaring flaws?

Bettmann / Getty Images

One theory is that growing up in a world dominated by vehicles puts them in a collective blind spot. In other words, car culture changes your brain. “It’s so endemic, it’s so pervasive, it’s so ubiquitous, that people don’t recognize just how much it is all around them,” said Ian Walker, an environmental psychologist at Swansea University in the United Kingdom. “And if it’s all around you, it’s shaping your perceptions.”

Walker coined the word “motonormativity” to describe this bias, which causes people to apply laxer moral standards to driving than other activities. Take the matter of air pollution. In 2023, Walker’s research found that 75 percent of people in the United Kingdom agreed with the statement that “People shouldn’t smoke in highly populated areas where other people have to breathe in the cigarette fumes.” But when two words were swapped — “People shouldn’t drive in highly populated areas where other people have to breathe in the car fumes” — only 17 percent agreed.

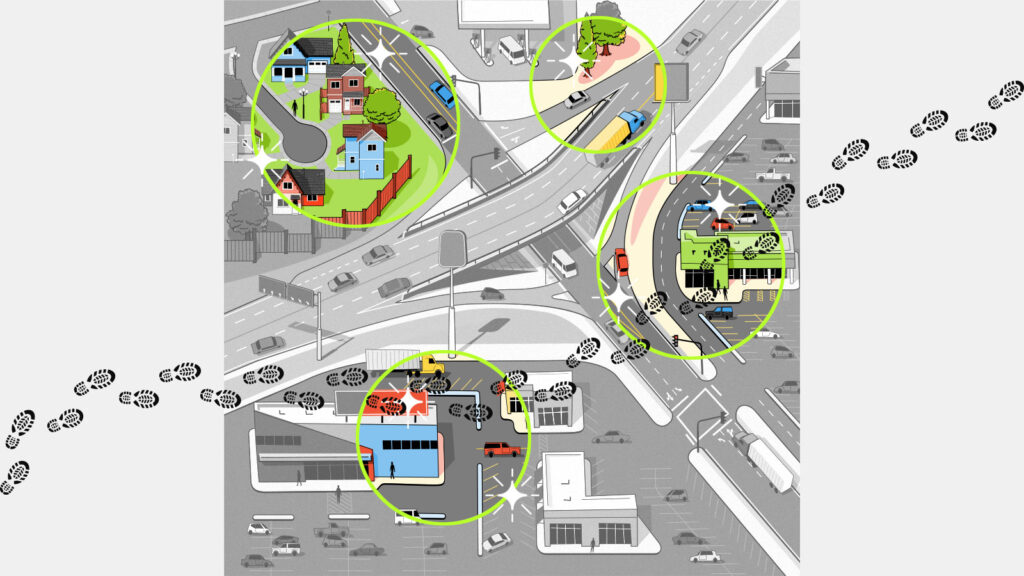

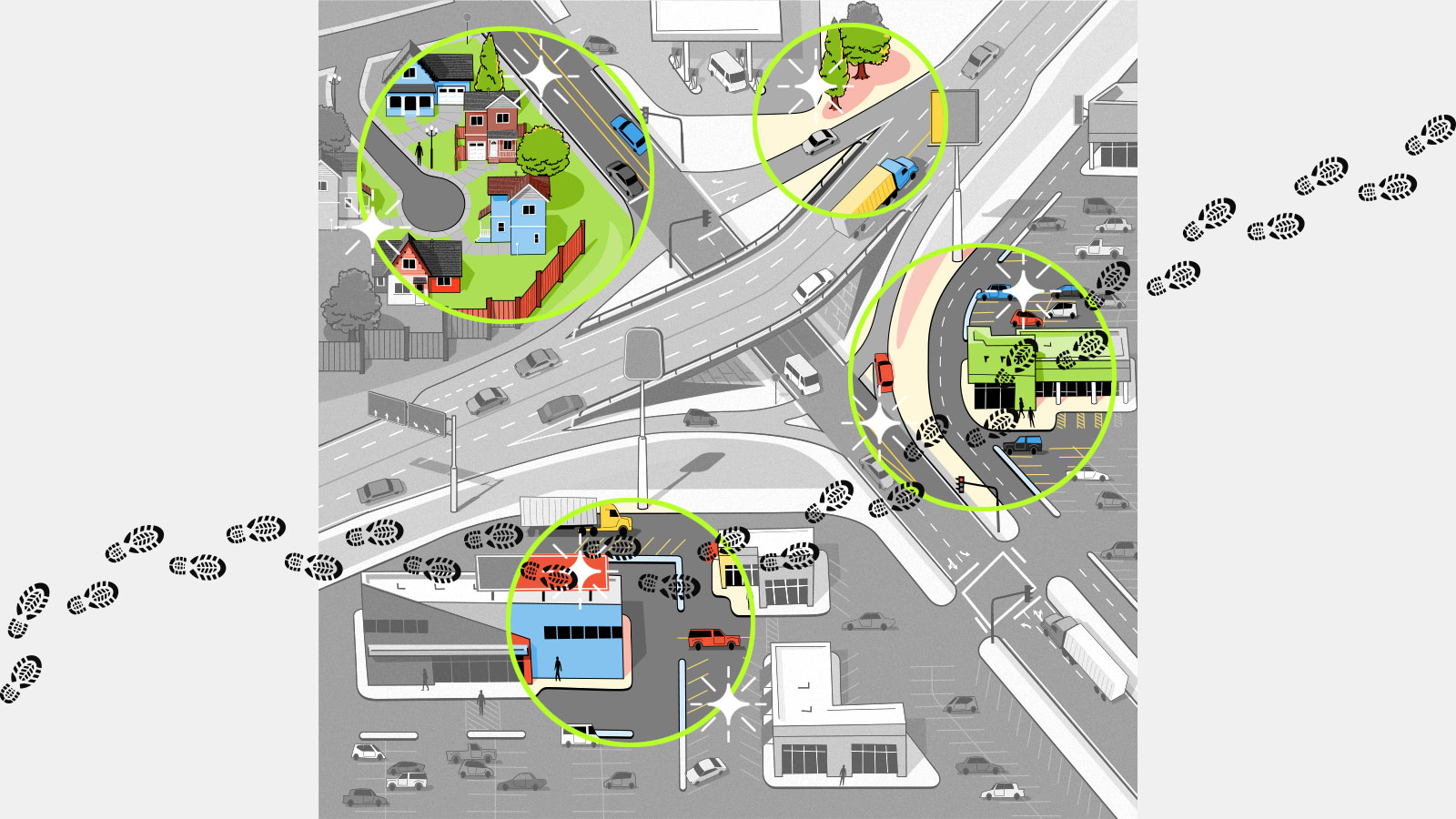

The bias can come from a conscious love for cars, or it can be learned subconsciously as people go about their days, living in places clearly designed for driving, as opposed to those built to make walking or biking easier. Walker’s study earlier this year found that people in the Netherlands, where biking is encouraged by urban design and much more common, have lower levels of pro-car bias than those in the United States or United Kingdom.

The reality is, without great transportation alternatives available, most people find it easier to ignore the risks of getting in a vehicle. “Driving a car or being a passenger in a car is by far the most dangerous thing that most of us do on a daily level,” said Sarah Goodyear, a co-author of Life After Cars (and a former Grist writer). “If you allowed yourself to think about how dangerous that is, it would be debilitating.”

As cars began to dominate the road — pushing out bikers, horse-and-buggy drivers, streetcar riders, and children playing in the street — the early critiques of them mostly faded away. But they never entirely disappeared.

A 1939 issue of the Superman comic book shows the superhero smashing cars after a reckless driver killed his friend. He terrorizes Metropolis’ mayor into rigorously enforcing traffic rules, and confronts an auto company executive about prioritizing “profits at the cost of human lives” before wiping out his automobile factory. A few decades later, Ralph Nader’s 1965 book Unsafe at Any Speed uncovered how the auto industry resisted safety features like seatbelts in favor of making flashy, visually appealing cars, sparking a national conversation that led to President Lyndon B. Johnson signing into law the first mandatory federal safety standards the following year.

Car companies poured a lot of effort into overcoming criticism. The auto industry spread the term “jaywalking” in the 1920s through a campaign to shame and blame pedestrians for traffic deaths, which included Boy Scouts reprimanding people who crossed the street wherever they wanted. In 1939, the same year Superman launched his war on cars, General Motors introduced a utopian vision of skyscrapers and seven-lane highways at the World’s Fair in New York, Futurama, which proved to be the most popular exhibit. It wasn’t long before those highways got built, and cars were sold as symbols of freedom and prosperity, with ads of families riding into the sunset on road trips. Even the phrase “America’s love affair with cars” was an industry invention, first coined in a Chevrolet ad in 1957.

Automakers still spend billions on advertising every year. Every football game on TV is punctuated by trucks rampaging through fragile deserts, woodlands, and streams, often accompanied by Will Arnett’s husky voiceover. What’s rarely seen is the reality of being stuck in traffic. “The industry isn’t just selling cars with those images,” write the authors of Life After Cars. “What they’re really hawking is a fantasy veiled in chrome and steel, the fantasy of power and control and independence. The American dream on wheels, no matter where in the world one lives.”

Cars have become intertwined with our lives, not just a practical way to get around, but an aspirational one, tied to our social status and identity. It’s a tough combination to break free from, one that would require overhauling the system that feeds us a message of car dependency: the design of streets, the laws that encourage driving, the advertisements, and more. “Until especially the public and the policymakers recognize there is actually a problem, I think we’re pretty stuck,” Walker said.

Walker has found that his idea of “motonormativity” resonates with people trying to make the transportation system more sustainable and more welcoming to other modes of travel, but not so much with the general population. (Street engineers, he says, are especially hard to convince.)

Getting people to listen to criticisms of cars may feel as daunting as ever, but Goodyear and Gordon say there are some promising signs. “I would say more people are ready than you might expect,” Gordon said.

Recent years have given people a glimpse of how the transportation system could change: The burst of outdoor dining after COVID-19 presented a picture of what streets could look like when cities didn’t prioritize cars. E-bikes, too, have become increasingly common, offering another way to get around. Drivers may find themselves open to other options as they struggle to pay for their vehicles, especially as more of them fall behind on their car payments. Policies are changing, too: Earlier this year, New York City implemented a congestion pricing plan that put a toll on driving in Lower Manhattan. Already, it has led to less traffic, more transit riders, fewer car crashes, and cleaner air.

Taken together, these trends help explain why books like Life After Cars are now on bookstore shelves for the public to peruse, not just marketed to bikers and transit nerds. “It’s almost impossible to imagine this book coming out 10 or 15 years ago from a major publisher,” Gordon said.

This story was originally published by Grist with the headline What we lost when cars won on Oct 28, 2025.